The late 1960s were a time of great changes in German Cinema. Starting with Volker Schlöndorff’s Young Törless (Der junge Törleß) and followed soon after by the almost experimental films of Fassbinder and Herzog, filmmaking in the West was experiencing a creative renaissance. In the GDR, filmmakers were still trying to maintain their artistic freedom, but it was getting more difficult every day. The revolutionary ideals that inspired and informed DEFA were now considered a threat to the system. With the banning of Kurt Maetzig’s The Rabbit is Me (Das Kanninchen bin ich), it was apparent that any attempt to push the limits would be met with repression.

The East German government was turning DEFA into a relic, completely out of touch with the public. More and more, people turned to the West for entertainment. Some attempts were made to placate people with films like Hot Summer, but even here, the filmmakers were treading on thin ice, politically.

Then, in 1971, Erich Honecker replaced Walter Ulbricht as the General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party. Ulbricht was beginning to make waves with the Russians. He got along fine with the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, but things weren’t so rosy between him and Khrushchev’s successor, Leonid Brezhnev. Honecker was a hard-liner whose approach to communism was more in tune with Brezhnev’s. Honecker wanted his leadership to signal a new page in the history of the GDR. Ironically, it’s only after the conservative Honecker came to power that the restrictions on film content in the East began to ease.

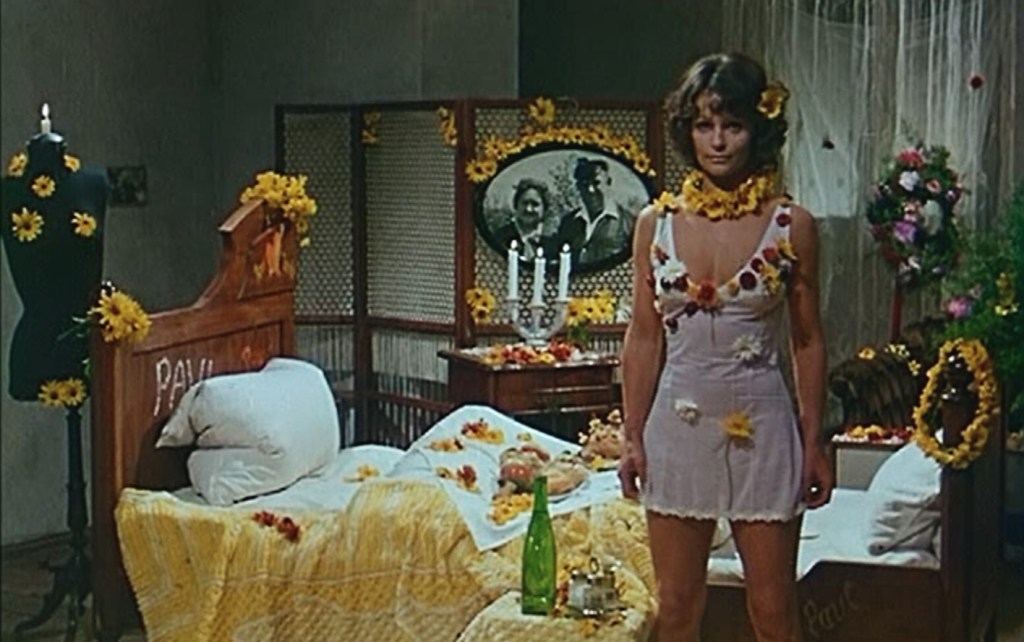

One of the first films to challenge the status quo was The Legend of Paul and Paula (Die Legende von Paul und Paula). The film follows the exploits of a blue-collar supermarket worker named Paula and her white-collar neighbor from across the way, an aspiring bureaucrat named Paul. It begins with the demolition of a building—a motif that recurs throughout the film, followed by a catchy little tune by the East German rock band, The Puhdys.

When we first meet Paula (Angelica Domröse), she is flirting with Colli (Christian Steyer), an Afro-headed hippie who runs the caterpillar ride at a carnival. She stares at him longingly until he whispers a suggestion in her ear. This is met with a slap, causing him to back off. We see in Paula’s eyes an immediate regret for her action, and she follows up by waiting after the carnival to meet with him. At the same time, Paula’s neighbor from across the street, Paul (Winfried Glatzeder), is at the shooting gallery, winning cheap prizes, which he promptly gives to Ines (Heidemarie Wenzel), the shooting gallery owner’s daughter.

It’s apparent from the start that both Paula’s and Paul’s choices for mates are bad ones. We sense that Colli will be a louse from the moment we see him, and when Ines smiles, she looks like a snake. Colli is incapable of commitment, and Ines is only interested in Paul after she learns of his earning potential. Paula soon has a baby boy with the repulsive Colli, who has moved in with her. Meanwhile, Paul marries Ines and also has a baby boy. For Paul, things come to a head when he returns from boot camp to discover another man in bed with Ines. Things are worse for Paula, who, upon returning from the hospital with her baby boy, finds Colli in the arms of a teenage girl.

The choice of Angelica Domröse to play Paula was inspired. She exudes sensuality and passion. Her earthy good looks are well-suited to the role of a working-class woman who is attractive without ever seeming out of place. Winfried Glatzeder is a little more problematic. When the film came out, the lantern-jawed Glatzeder was referred to as the East German Jean-Paul Belmondo, but that is stretching things a bit. He’s a goofy-looking guy. He also has the unenviable task of playing the stodgier half of this relationship.

Paula seems to have no impulse control. Her choices are not predicated on any kind of logic or even basic sense. She works entirely from her emotions, and like her emotions, she can change directions on a whim. Paul, on the other hand, is all about control. The parameters of his job are never fully spelled out, but it’s suggested that it’s government work. Appearances and protocol are important to Paul. In one scene, he takes Paula to an open-air concert. Moved by the music, she starts applauding after the first movement. When Paul tries to stop her, telling her that clapping after the first movement is simply not done, she ignores him and continues to clap.

The overt message of the film is that it is better to feel and hurt than to rationalize yourself into numbness. In some scenes, the action is based on what is going on internally rather than actual events. There are subtler messages at work in this film, which were not lost on the East German public. In the scene where Paula entices Paul over to her place for sex, Paul asks about the musicians sitting on the couch; the scene then cuts to three musicians sitting on the couch. “Oh, them,” Paula says, “they can’t see us.” The scene cuts back to the musicians, now wearing blindfolds. To the Western observer, this seems like a surrealistic affectation, but Paula is referring to something more common in East Berlin: microphones. Paula is reassuring Paul that the Stasi may have the room bugged, but they won’t see anything (the three musicians also appear to be the same three men that Paul works with). What follows is one of the most unusual sex scenes ever committed to film, involving a floating bed, dead ancestors, and a song that uses kite-flying as a metaphor for sex.

The film was a big hit and remained popular up until many of the lead actors left for the West after the expatriation Wolf Biermann. At that point, the film was officially banned, but it was too late. As soon as the Berlin Wall came down, the film found its way back into the movie houses and is one of the films that signaled the Ostalgie movement of the 1990s. Lake Rummelsburger See—where Paul and Paula go with Saft and Paula’s daughter—has been renamed “Paul and Paula beach.” Thanks to this film, The Puhdys became one of the most popular rock bands in East Germany, and the songs Geh zu ihr (“Go to her”) and Wenn ein Mensch lebt (“If a man lives”) remain popular to this day.

If you like what I do here and would like to let me know, you can buy me a cup of coffee by clicking on the button to the left.

© Jim Morton and East German Cinema Blog, 2021. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jim Morton and East German Cinema Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

“Martin (Jürgen Frohriep), an Afro-headed hippie that runs the caterpillar ride at a carnival.” That is incorrect. Paula met Martin (Jürgen Frohriep) at a nightclub, alongside Paul. They kissed/danced, etc, but she ended up with Paul that night. The hippie was played by Christian Steyer.

Good catch, Aaron! I’ve fixed it in the text, along with a few other edits. That was one of my very first posts on the blog and I was still just barely familiar with the DEFA catalog. I certainly would have recognized Jürgen Frohriep now.

No Problem. Jürgen Frohriep was pretty big. He played the iconic Oberleutnant Hübner on Polizeiruf 110. (long-running police series) My German girlfriend claimed the East German girls called him “Hübschi”. He was a veteran actor. In the film he ended up with Eva Marie Hagen. She was also amazing, being a celebrated opera singer and actress. She was married to dissident Wolf Biermann and mother to punk rocker Nina Hagen. Ironically Jürgen and Eva Marie played unflattering characters, in the film. There are some great interviews and documentaries on these people on YouTube. You can also catch full episode re-runs of Polizeiruf 110 from the 70s and 80s, on Youtube. Glad I could help.