As mentioned elsewhere on this blog, the period between the building of the Berlin Wall and the 11th Plenum was a golden age for film in East Germany. The authorities were determined to prove that building the wall was not intended to repress the population, but was intended as an “anti-fascist protective barrier” (antifaschistischer Schutzwall) that would allow East German filmmakers greater artistic freedom without subversion from the west. Films that would have been deemed too experimental or arty before the Wall were approved now, and DEFA’s directors took full advantage of this change in policy. Small wonder, then, that any list of the best East German films shows a noticeable concentration of films made during this period.1

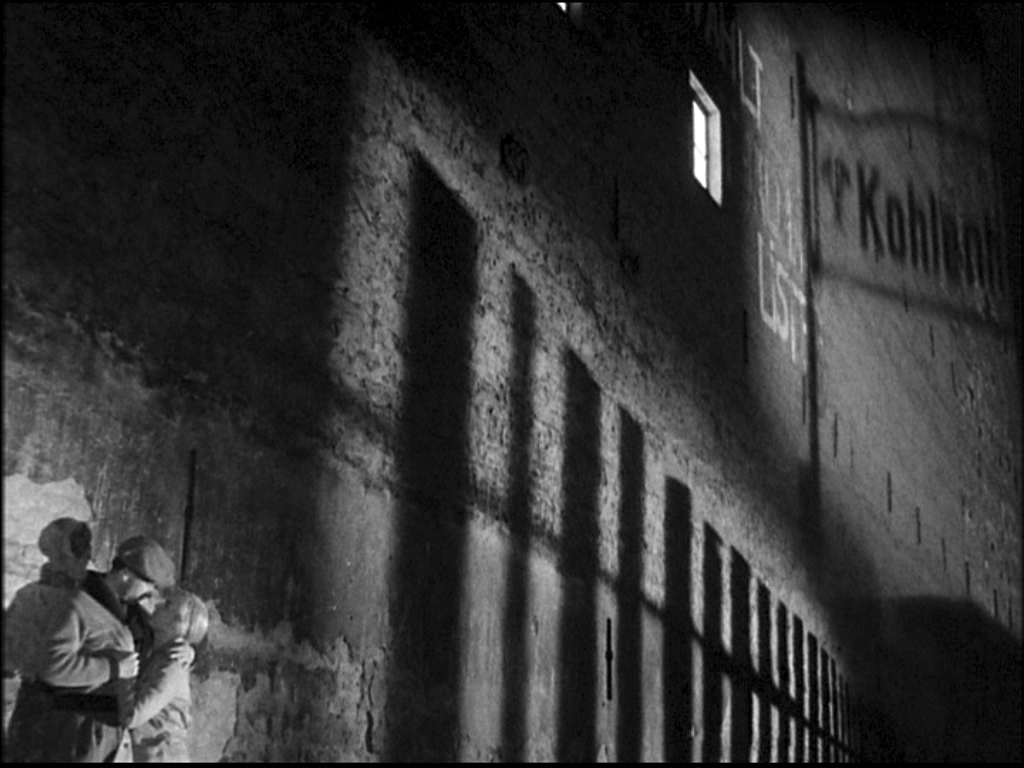

One of the first to take full advantage of DEFA’s new policy was Frank Beyer, a director on any short list of great East German directors, and the only one from the GDR to have an Oscar nomination (Jakob the Liar). With Star-Crossed Lovers (Königskinder), Mr. Beyer kicks things into high gear with vivid cinematography and an artist’s eye for frame composition. It is a dazzling film from a brief but exceptional time for East German cinema.

Star-Crossed Lovers is the story of three childhood friends—Magdalena, Michael, and Jürgen. Michael and Magdalena are in love, but the fates conspire to keep them apart. Jürgen, a timid conformist, has lusted after Magdalena since childhood, but there is never really any romantic tension here—Magdalena loves Michael, Michael loves her, and poor Jürgen remains the odd man out. When they get older, Michael becomes active in the KPD (the German Communist Party) and Magdalena assists him. Meanwhile, Jürgen takes the path of least resistance and joins the SA. He still loves Magdalena, but, as one might imagine, his employment choice does nothing to improve his standing in her eyes.

The story is told in flashbacks, with the present-day action taking place during the final days of World War II. Magdalena is working with the Russians to provide aid to their troops on the front lines, while Michael is conscripted into the infamous Strafdivision 999 (Penal Battalion 999), Hitler’s remarkably ill-conceived attempt to use prisoners as soldiers. There he meets up with Jürgen, who has been assigned as an officer in the battalion.

The German title for the film comes from the folk song, “Es waren zwei Königskinder” (There Were Two Royal Children), which tells the story of a prince and princess who are kept apart by waters that separate them. Of course, the “waters” in this case Nazism and WWII, but Beyer is a sophisticated filmmaker and he reflects the idea of separation by water several times in several ways. Part of the fun of this film is spotting these references. Things end badly in the song, and the film hints at a similar tragedy, but Beyer leaves things open to interpretation.

Playing Magdalena is Annekathrin Bürger. I’ve talked about Ms. Bürger in previous post (see Hostess and Not to Me, Madame!). Ms. Bürger started working films at eighteen after being discovered by Gerhard Klein, but 1962 was a banner year for her. She starred in two of the best films from that year—this one and The Second Track. After marrying Rolf Römer, Ms. Bürger often starred in films he directed. She continues to work in films.

Michael is portrayed by Armin Mueller-Stahl, who was just coming into his own when this film was made. He had appeared in some TV movies during the fifties, but it was his role in Five Cartridges that brought him to the big screen. Star-Crossed Lovers was his second feature film, followed a few months later by And Your Love Too. He starred in several classic DEFA films, including Naked Among Wolves, Her Third, Jakob the Liar and The Flight. In 1976, he joined other popular film stars in a protest against the expatriation of Wolf Biermann. As with the others who signed the protest, he found that job opportunities had dried up, so he did what many of the others on the list did also, and moved to West Germany. For Mr. Mueller-Stahl this proved to be an especially auspicious move. There, he met up with Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who cast him in Lola and Veronika Voss; and with Niklaus Schilling, who cast him in Der Westen leuchtet (The Lite Trap). He began to get more work in West Germany, but the big break came when Costa-Gavras cast him as the Grandpa with a secret in The Music Box. Other films followed quickly, including Barry Levinson’s Avalon, Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth, and Steven Soderbergh’s Kafka. Mr. Mueller-Stahl is a true renaissance man. Besides being an actor, he paints, writes, and plays a mean fiddle. Of late, he has been concentrating on these other pursuits over acting.

To play the sad-sack Jürgen, Mr. Beyer cast Ulrich Thein. Mr. Thein, more than any other star in East Germany, was born to be an actor, his father was a theater bandleader. Although his father died when he was only four years old, the young Ulrich continued in his father’s footsteps, studying music and working in theater. In 1951, he joined the world-famous Deutsches Theater Berlin, where he continued to perform until 1963. Ironically, although he played the unloved man in this film, it was he who was in a relationship with Ms. Bürger at the time. During the sixties, Mr. Thein added film director to his list of talents—at first in TV movies, then later in feature films. After the fall of the Wall, he found that most of the films he was offered were lousy. In his words, “I won’t make the shit producers are offering me.” (“Ich will den Scheiß nicht machen, der mir von einigen Produzenten angeboten wird.”). He retired from filmmaking in 1992, and took up teaching.

To shoot the film, Mr. Beyer used his long-time collaborator, Günter Marczinkowsky. Like many of the better cinematographers at DEFA, Mr. Marczinkowsky came from the technical side of film, having work as a photo lab technician and a projectionist before starting at DEFA. He was assistant to the famous Robert Baberske, whose Berlin: Symphonie of a Great City remains a classic example of pure cinema. After Beyer’s Traces of Stones was banned, Mr. Marczinkowsky was relegated to work on TV movies—a common fate for anyone who found their work in the crosshairs of the 11th Plenum. He returned to features films from time to time, most notably with Abschied (Farewell) and Jakob the Liar, but most of his later work was for the small screen. Sadly, his career ended with the collapse of East Germany.

Of the films from East Germany, I would have to categorize this one as the best film that is not available with English subtitles. I suspect this is only temporary. It’s too good a film to go unrecognized for much longer.

Buy this film (German only, no subtitles).

1. It probably didn’t hurt that during the same period, West Germany’s film industry was gaining a reputation for making lousy movies. So much so that, in February of 1962, a group of young West German filmmakers at the International Short Film Festival in Oberhausen released the Oberhausen Manifesto, stating that “conventional films are dead,” and calling people to challenge the film industry’s conventions, and free it from the control of commercial interests.